Start in the missing middle

If you work in a complex, technical organisation – an engineering firm, an energy utility, a transport operator – you spend much of your day translating. Executives speak in outcomes. Engineers speak in systems.

For communications professionals, that translation gap can be a challenge. When the corporate story stays too lofty, it lacks proof and credibility. When the technical story is too deep, it loses meaning. Building reputation demands both: the substance of subject-matter expertise, and the simplicity that makes it understandable to an array of stakeholders.

That is the missing middle – the translation layer where understanding, credibility and momentum should live, but too often don’t.

Why the missing middle appears

Picture a spectrum. At one end: purpose, positioning and big-picture outcomes. At the other: standards, acronyms, componentry, processes and risk controls. What should live in between both ends is something delivering believable claims and plain-English explanations that non-specialists can use.

In engineering-heavy environments, the gap often appears because precision matters. Teams are rightly protective of detail. Oversimplify, and you risk misrepresenting the truth. The goal isn’t to dilute complexity, but to add context — what’s changing, why it matters, who benefits, what the trade-offs are, and how we’ll know it worked.

Some organisations have found effective ways to bridge that space – keeping technical accuracy while giving the story real-world meaning. Engineers Australia has used its editorial platform, create, to position its engineers as national thought leaders in specialised fields, rather than technical commentators. In one feature, transport expert Scott eLaurent translated the complex policy mechanics of road pricing into a human story about fairness and the trade-offs that affect us all. eLaurent illustrates the inequity with an example anyone can understand: “If you live in an outer suburb, near a toll road, you’re going to pay a lot. But if you can afford to buy close to the city, you probably don’t use a toll road to get to work. So even though you [might be] much wealthier and can afford to pay more, you’ll be paying very little. Some people spend more per week on tolls than they do buying groceries.”

What lives in the middle

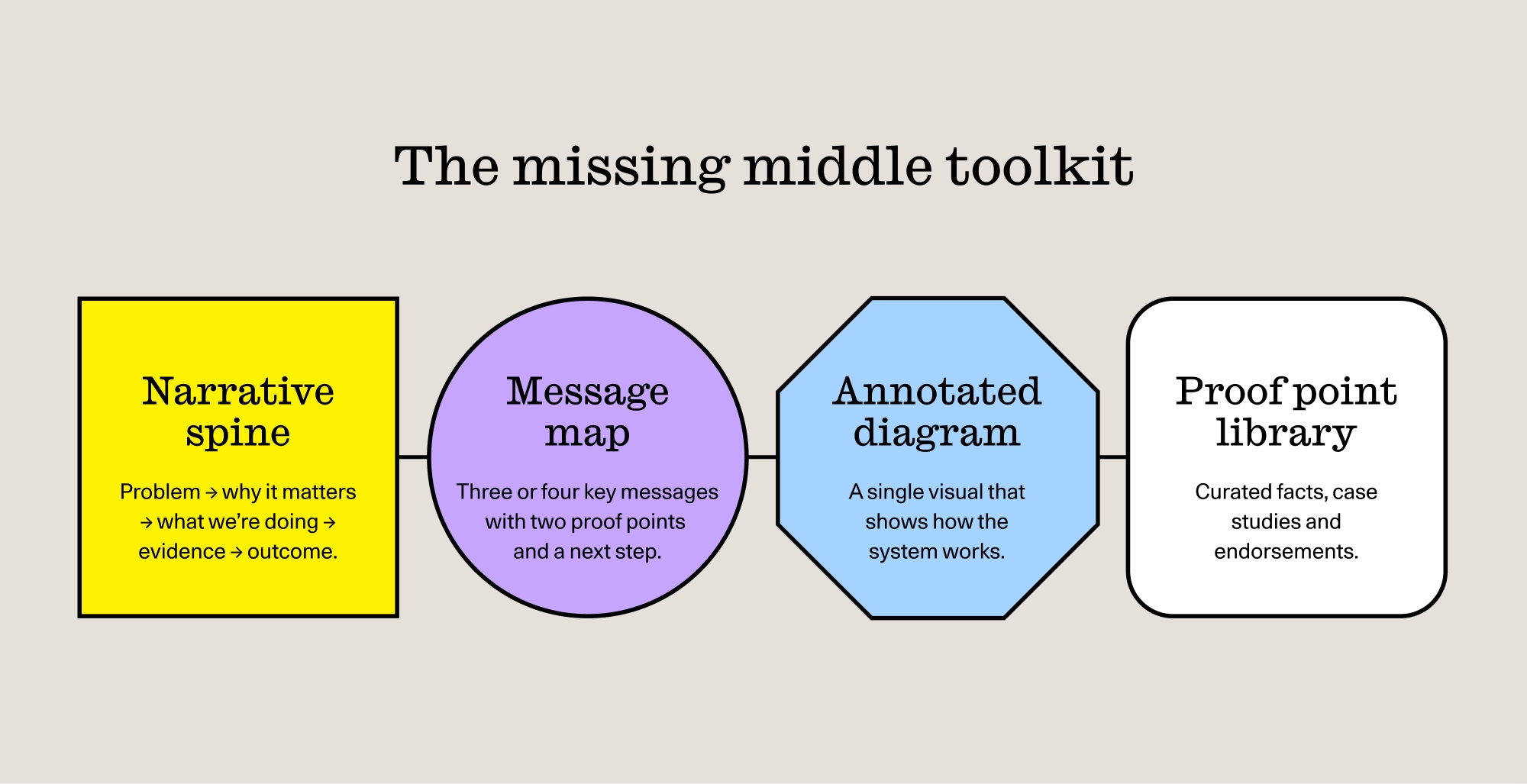

Filling the gap doesn’t require creating more content. What’s needed is a small, durable toolkit that engineers and executives both recognise as useful:

- A narrative spine. Problem → why it matters → what we’re doing → evidence → outcome. Use it for everything from a media note to a town hall.

- A one-page message map. Three or four priority claims for the quarter, each with a plain-English line, two solid pieces of proof, and a next step.

- An annotated diagram. One graphic that shows how the system works or how value flows, labelled for a smart non-expert.

- A collection of proof points. Sourced facts, case studies, approvals and third-party endorsements, versioned and maintained like any other asset.

These artefacts prevent teams from defaulting to either slogans or specs, and make it easier to reuse and adapt communications across the organisation.

How to speak to the middle (without losing rigour)

Writing for the middle starts with stakes, not statements. “We’re cutting unplanned downtime by 30% by replacing X and retraining Y”, says far more than “We’re modernising our network.” It grounds a goal in something measurable and concrete.

Credibility also grows when you acknowledge trade-offs. Constraints around budget, standards or timelines don’t undermine a message; they make it believable. The same applies to language: clear, active verbs such as inspect, replace, verify and approve carry more weight than vague ones like enable, leverage or optimise.

Keep numbers simple enough to stick. A single memorable metric often tells the story better than a cluster of percentages no one remembers. And when you find a line that works, make it work hard. The best writing for the middle is reusable – a phrase that fits as comfortably in a project update as it does in a press release.

Calibrate by audience, not ego

Hold two versions of the same message:

- For non-experts: move one level up from detail to stakes (what’s at risk, who benefits, what changes).

- For experts: move one level down from slogans to system change (what’s being altered, how failure modes are addressed, how success is measured).

"Use the 20-second test: if a smart non-expert can’t tell what’s at stake within 20 seconds, it’s not ready. Then run the expert check: does it respect the constraints a technical peer would expect to see?"

Finding your middle, fast

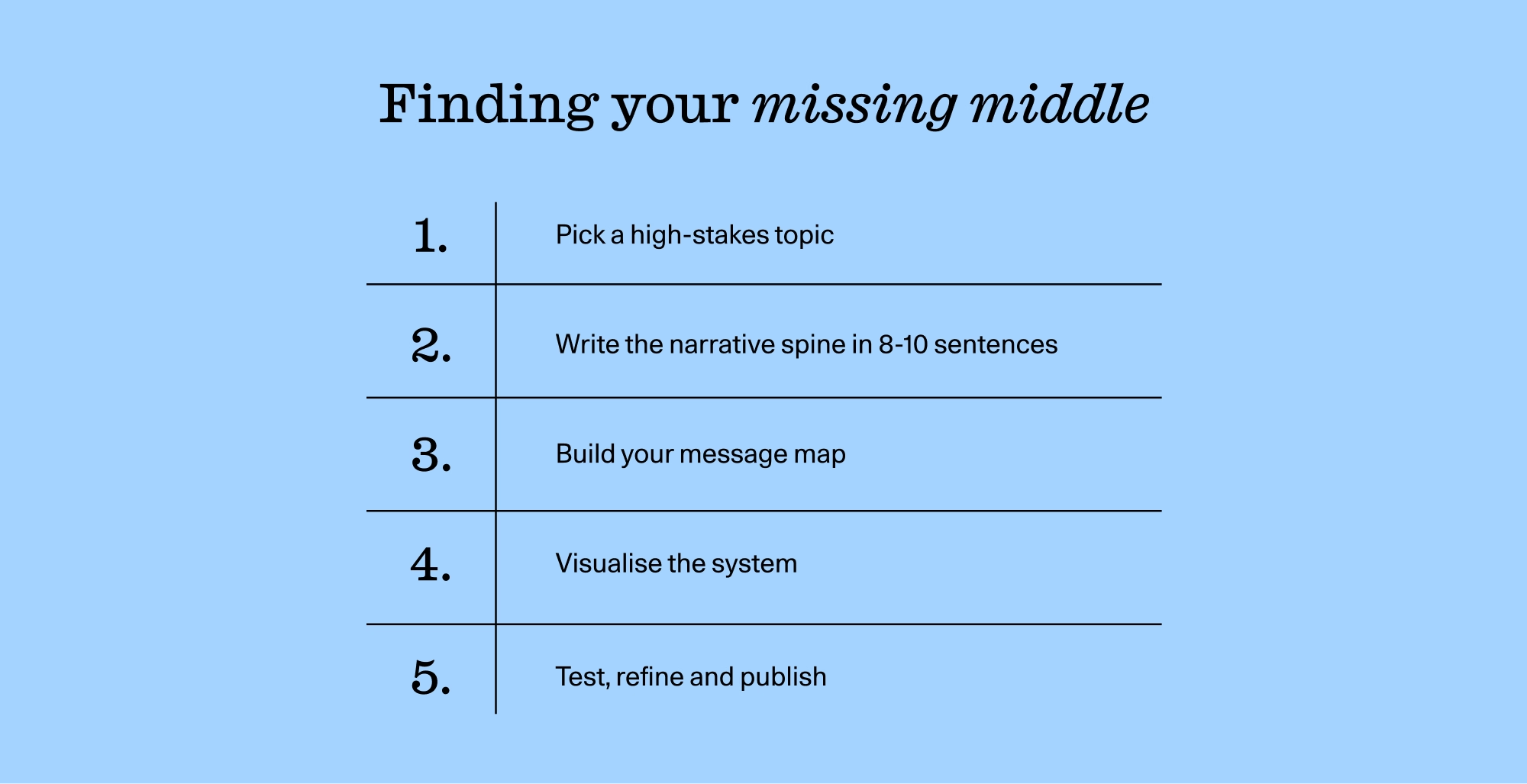

Pick one high-stakes topic – a regulatory shift, asset upgrade or sustainability commitment – and do three things:

- Draft the narrative spine in 8–10 sentences.

- Build a one-page message map with two proof points per claim.

- Add one annotated diagram that a non-expert can follow.

Share these with three people: a journalist, a customer and a policy contact. Note where they stall or push back, tighten the language, strengthen the evidence and publish across your internal and external channels.

Complex organisations earn reputation when they make meaning without losing precision. Build the bridge in the middle, and your brand can stay ambitious, your engineering can stay rigorous, and your reputation can finally reflect both.